Class Anthozoa - Coral

Class

Anthozoa

|

Also

see: | |

|

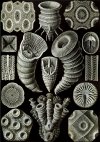

Only a few CaCO3-secreting corals or coral-like organisms are known from the early Cambrian (e.g., Sorauf and Savarese 1995), and the Cothoniida, are known from the middle Cambrian. It was not until the Ordovician that mineralized corals became prodigiously important to marine ecosystems. By the middle Ordovician, the Tabulata, and Rugosa corals, and the smaller Heliolitida were widely prevalent. Despite the appearance of corals during the Ordovician, reef ecosystems continued to be dominated by algae and sponges and in some cases by bryozoans. However, there apparently were also periods of complete global reef collapse due to global disturbances.

The

also extinct Rugosa or Rugose coral were ubiquitous from the middle

Ordovician to late Permian. Solitary forms (i.e., solitary polyps)

are commonly called horn corals owing to their horn/conical-shaped

chamber having a From

the middle Ordovician in the Paleozoic major coral groups were

contributors to massive reef systems, while stromatolites reefs

were in steady decline. The Heliolitids The

scleractinians (Order Scleractinia) appeared in the Triassic.

In fact, all corals after the than the PT extinction as well as

all extant corals, belong to the Scleractinia. They are differentiated

from the Rugosa by their patterns of septal insertion where the

scleractinian septa are appear in sets of six, maintaining a hex

symmetry throughout life. The scleractinian corals are markedly

different than the Paleozoic rugose corals, which leads scientists

to believe they evolved separately from anemones instead of from

the earlier Rugosa. The scleractinians have formed great Anthozoans do not have a medusa stage in their development as do other cnidarians. Rather, they release sperm and eggs that form a planula that attaches to a surface on which they grow. A coral head contains thousands of genetically identical polyps, each typically a few millimeters in diameter. Over thousands of generations, the polyps lay down a skeleton that is characteristic of their species, and recognizable as fossils. Polyps are usually a few millimeters in diameter, and are formed by a layer of outer epithelium and inner jellylike tissue known as the mesoglea (see figure to right). They exhibit radial symmetry with tentacles surrounding a central mouth, the only opening to the stomach or coelenteron, where food is ingested and waste is expelled. The polyp grows by extension of vertical calices that are sometimes septated to form a new base plate. Over numerous generations the extensions form the large calcareous structure from which coral reefs are comprised. The calcareous exoskeleton is built by the deposition of the mineral aragonite by the polyps from calcium in seawater. References:

|

||

Fossil

Museum Navigation: Fossils Home Geological Time Paleobiology Geological History Tree of Life Fossil Sites Fossils Evolution Fossil Record Museum Fossils |