Fossils of the Solnhofen Limestone - A Jurassic

Konservat Lagerstätte

in Germany

The

Solnhofen Limestone ranks as one of the most most famous Lagerstatte

in the world. This fossil site in the state of Bavaria in Germany

has yielded an amazing diversity of fossil organisms, often

deposits known for the exceptional preservation of fossilized

organisms, where the soft parts are often preserved (a Konservat-Lagerstätte),

provides a snapshot of Jurassic life

155 million years ago. The most famous are the eight fossils

of the first bird known in detail, Archaeopteryx.

The first Archaeopteryx fossil was discovered in 1860, a single

feather. The next year a very complete example was found and

sold to the British Museum. The next specimen was discovered

sixteen years later, and is known as the Berlin specimen. It

is considered by some to be the most valuable fossil in the

world today. With its combination of characteristics of reptile-like

teeth and tail with the feathers of a bird, it was a quintessential

missing link that supporters of Charles Darwin could refer

to as proof of the theory of evolution. In the subsequent

140 plus

years since the first bird was found, only six more have been

added to the handfull of examples.

The

Solnhofen Limestone ranks as one of the most most famous Lagerstatte

in the world. This fossil site in the state of Bavaria in Germany

has yielded an amazing diversity of fossil organisms, often

deposits known for the exceptional preservation of fossilized

organisms, where the soft parts are often preserved (a Konservat-Lagerstätte),

provides a snapshot of Jurassic life

155 million years ago. The most famous are the eight fossils

of the first bird known in detail, Archaeopteryx.

The first Archaeopteryx fossil was discovered in 1860, a single

feather. The next year a very complete example was found and

sold to the British Museum. The next specimen was discovered

sixteen years later, and is known as the Berlin specimen. It

is considered by some to be the most valuable fossil in the

world today. With its combination of characteristics of reptile-like

teeth and tail with the feathers of a bird, it was a quintessential

missing link that supporters of Charles Darwin could refer

to as proof of the theory of evolution. In the subsequent

140 plus

years since the first bird was found, only six more have been

added to the handfull of examples.

The

discovery of the wonderful fossils

of Solnhofen may be attributed

to the longtime uses to which the "plattenkalk" has

been used. This is a German word that seems more appropriate

than the English "platy limestone". Plattenkalk was

used as early as the Stone Age for making drawings and colored

murals due to its softness. The flat, regularly shaped material

was suitable for paving roads and building walls, something

done by the ancient Romans  who

for a time held sway over the region. In the Middle Ages, the

stone was used as floor and roofing material. The mosaic floor

of the church of Hagia Sofia in Istanbul was made of limestone

from the region. Artisans also used the material in the making

of bas-relief sculptures and headstones. A decisive turning

point in the history of the area was the discovery in 1673 by

Alois Senefelder that the fine-grained material could be employed

in lithography, a use that caused quarrying to skyrocket. Although

the heyday of lithography only lasted a hundred years or so,

it was the single most important impetus in the discovery of

fossils.

who

for a time held sway over the region. In the Middle Ages, the

stone was used as floor and roofing material. The mosaic floor

of the church of Hagia Sofia in Istanbul was made of limestone

from the region. Artisans also used the material in the making

of bas-relief sculptures and headstones. A decisive turning

point in the history of the area was the discovery in 1673 by

Alois Senefelder that the fine-grained material could be employed

in lithography, a use that caused quarrying to skyrocket. Although

the heyday of lithography only lasted a hundred years or so,

it was the single most important impetus in the discovery of

fossils.

The

fossils have always been prized by local residents because of

their beauty. As those most intimately associated with the limestone, the quarrymen were obviously those who were

responsible for their discovery. At first, quarry owners allowed

the workers to keep the fossils they found, but as interest

in them (and consequently, value) grew, this practice stopped.

The variety and number of fossils known is deceptive. The occurrence

of fossils is quite low. Indeed, a worker can quarry for an

entire day and find not a single one. The hundreds of years

of quarrying are what make them seem so apparently common.

with the limestone, the quarrymen were obviously those who were

responsible for their discovery. At first, quarry owners allowed

the workers to keep the fossils they found, but as interest

in them (and consequently, value) grew, this practice stopped.

The variety and number of fossils known is deceptive. The occurrence

of fossils is quite low. Indeed, a worker can quarry for an

entire day and find not a single one. The hundreds of years

of quarrying are what make them seem so apparently common.

The

sheets of limestone are so regular that we can only conclude

that they were deposited in a calm environment. The deposits

were evidently laid down under a stable body of water that had

some connection to the Tethys Sea. Sponges and corals grew on

rises in this sea, forming lagoons. In fact, remnants of a coral

reef can be found in the area to the south of Solnhofen. The

region must have been near land, however, due to the discovery

of insects such as wonderfully-preserved dragonflies. Assuming

that Jurassic coral reefs grew in modes similar to those of

today, the surface of the reefs would have been only 10 meters

or so under water. The maximum depth has been estimated by some

to have been 60 meters (200 feet).

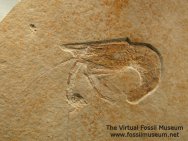

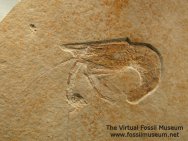

These

isolated lagoons would have been quite stagnant due to little

exchange of water with the sea. Anoxic conditions would have

been ideal for preventing destruction of organisms that found

their way into the lagoons. Some evidently survived for short

periods. One of the most famous examples of this are the horseshoe

crab "death spirals' that exist in which a spiral trackway

has been preserved with the defunct arthropod in the center,

presumably preserving its last efforts at survival. The theory

most often proposed for the toxicity of the waters has been

that of hypersalinity, the excessive concentration of salt.

If the area were hot and dry, with little runoff from the land

to the north, conditions would have been ideal for promoting

excessive evaporation of water with concomitant increase in

the salinity in the lagoons. The dense brine would collect in

the bottom of the pools, excluding most life, as sensitivity

to even minute changes in density has been seen in many marine

organisms. Once an organism had been washed into the lagoon

by the action of a storm, it would quickly succumb to the toxic

conditions that existed within. The hypersaline, anoxic floor

was ideal for the preservation of the body, often even leaving

evidence of soft tissues.

These

isolated lagoons would have been quite stagnant due to little

exchange of water with the sea. Anoxic conditions would have

been ideal for preventing destruction of organisms that found

their way into the lagoons. Some evidently survived for short

periods. One of the most famous examples of this are the horseshoe

crab "death spirals' that exist in which a spiral trackway

has been preserved with the defunct arthropod in the center,

presumably preserving its last efforts at survival. The theory

most often proposed for the toxicity of the waters has been

that of hypersalinity, the excessive concentration of salt.

If the area were hot and dry, with little runoff from the land

to the north, conditions would have been ideal for promoting

excessive evaporation of water with concomitant increase in

the salinity in the lagoons. The dense brine would collect in

the bottom of the pools, excluding most life, as sensitivity

to even minute changes in density has been seen in many marine

organisms. Once an organism had been washed into the lagoon

by the action of a storm, it would quickly succumb to the toxic

conditions that existed within. The hypersaline, anoxic floor

was ideal for the preservation of the body, often even leaving

evidence of soft tissues.

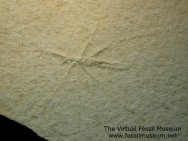

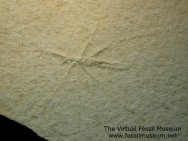

Storms

would have often brought in a suspension of finely-dispersed

lime. Such storms would have brought in the amazing diversity

of life we know from the region: pterosaurs, dinosaurs like

Compsognathus and Archaeopteryx, dragonflies, and other insects,

fish, turtles, crinoids, starfish, jellyfish, ammonites, worms,

plants, and many, many more. The number of species found exceeds

500. The limestone deposits of Solnhofen open a door closed

to us over 150 million years ago, affording us a look at a wonderful

diversity of life from both the land and the sea of the Jurassic.